The intersection of these three shows the procedures by which Muslim men are denuded of their masculinity. There are, of course, significant exceptions. Somewhat further afield, the work of Daniel and Jeganathan details the voices of those who have been afflicted by violence and the difficulties of locating these voices within social relations. In the process, we are forced to revise our understanding of the stability and coherence of social structures.

Much less is known of the complexities of gender for wounded bodies, especially processes by which adult males, caught in violence, are denuded of their masculinity. This article attempts an initial elaboration of how, through collective violence, masculin- ity is unmade and of its link to local public spaces and, through it, the nation- state. While I do not argue for an inherent connection between individual and political bodies, I show that this relationship is tied to the idea of national borders and segregated spaces.

Men and Masculinities, Vol. The city of Bombay renamed Mumbai in November was in a state of virtual civil war until the third week of January From the middle of , I began collaborative fieldwork in a slum in Mumbai, called Dharavi. Our intention was to study the affects of the violence of and and to map its trajectories in the lives of various residents of the slum.

The effects of violence have also been documented Mehta ; Mehta and Chatterji The one fact that was clear in our fieldwork was that the understanding of violence could not be framed in a unitary way. Much like the lives of the people in Dharavi, where old and new solidarities collide, where bound- aries between intimate and public spaces are not sharply drawn, and where bricolage in social relationships is part of everyday life, our fieldwork com- bined aggregate and fragmentary perspectives on violence.

All the inhabi- tants agreed that there was violence in Dharavi in and , but vested interests, personal histories, ideological positions, and propaganda together ensured that a definition of violence was at best a powerful fiction or nego- tiated half truth. While descriptions of violence in and were dif- ferent from those provided by the same set of people in , they showed that violence was not an effect that happened to passive recipients. It was and continues to be a process that is braided into the texture of everyday life.

And yet, we find a common weave in the stories of residents, a leftover of the violence of and This article aims to discuss the leftovers. This remainder, I argue, is an image of the territorial borders of the nation-state as it merges with both neighborhoods in Dharavi and bodies of groups of people who are seen as alien and other. The links between the borders of the nation-state and neighborhoods in Dharavi is charted in the narratives of Dharavi residents. These narratives are not stable accounts of the violence, nor are they marked by an internal consistency, and yet, the Downloaded from jmm.

Perhaps, the revenant of violence cannot be obliterated from accounts that talk of housing, work, and public life of the neighborhood. In trying to understand how the danga marks these issues of daily living, this article opens the possibility of thinking of everyday life as allegoric remem- brance. By this, I mean that talk of the danga in the everyday contexts of domesticity, work, and public life highlights an open declarative speech about the other.

This speech is allegorical to the extent that stories of the danga, as they reflect on the past, also tease out the political present. In fact, they fill in the temporal gap between past and present and often point to a potential future. This article is in three parts. The first shows how the effects of violence alter the public space of the neighborhood.

The second describes how the neighborhood imaginatively encapsulates the nation. The last section dis- cusses the processes by which this imagination is marked on male bodies. This emerges when Muslim men describe how this mark functioned as one of identity during the danga. You see, the roads were under constant threat. Groups of boys from outside would wait on the roads. If they found anyone, they would strip him to dis- cover his identity.

They [Hindus] call us katua, people who are not male. Two Muslim brothers who were textile entrepreneurs in Dharavi reported this conversation to us in They had suffered extensive losses during the violence, and one of them had briefly returned to his village in Uttar Pradesh. In June , I met the younger brother over an extended conver- sation on the economic and political conditions in Dharavi. Of course, Dharavi has improved, but sometimes I recall those days of dhashat [terror]. I do my work from home. I take care to teach my Downloaded from jmm. No, no, not at all. But we were made naked in public.

They took down our pants and called us Pakistani, as if my nationality is on my linga [penis]. After the danga, the chawl committee [neighborhood association] was made and met those of us who remained. I went to those meetings. The police told us that we could live freely now. But live with what? Earlier I had a big house, now a small one room. Sometimes when I walk along these roads, I remember how some of us were stripped.

The same members of the chawl committee and the police did it. I saw this; we all saw this, more often than I care to remember. I was changed by the terror. I can no longer think of these galis [alleyways] as my own. How were these galis your own? In answer, he asked me to take a walk with him. Outside his house, we walked toward a square Shamim called this the maidan, or public ground in the center of which is a water pump.

A boy was drawing water, while two others were trying to fly kites. On one side of the square, a few men were putting sheets of cloth into large iron pots, filled with boiling dye water. He asked one of them to get bales of cloth from his house and to begin coloring them. He explained that before , he would not take on dyeing work, as the market and consequent profit margins for such cloth were limited to semiurban areas of Maharashtra.

Before the danga, we all had our own sthan [place]. Opposite this maidan [pointing to a row of shops], Ajim had his tailor shop. He lived with his wife and children. He ran away during the danga after his shop was looted. Madhav lived next to him. He has moved to greater Mumbai. Often we would have kite-flying competitions during Id and Diwali. It was said that during Id, this was the biggest marriage market in Dharavi.

Initially hesitant, he allowed himself to be persuaded to drink beer and then continued. In hindsight, I can say only that his speech was sober and angry, interrupted frequently by those he thought were within hearing distance. It was almost as if he was asserting the rule of silence as a public right of protection against strangers. Workers are unreliable and you have to be careful about your behavior and what you say to them in the maidan. I give my orders at home, and I pay them by the day there. One must be silent and in control.

Service people, all Maharashtrians, have taken their place. Was there any violence in the maidan? During the danga, Muslims were brought here and stripped. Even now, I find it difficult to talk about what they did. The maidan was called the Majlis-e-Pakistan [the parliament of Pakistan]. What happened after Muslims were stripped? Thrashed and kicked on our genitals. Whatever you can imagine, I can only say it was worse. The interaction of violence and public geography pulls in two directions; one is a withdrawal from the public into the domestic; the other is a change in the terms of belief about secular life as it is lived out in neighborhoods.

Secularism, in the hybrid discourse of modernity in contemporary India, is not simply a political idiom but a kind of civil religion that recognizes and allows for the practice of different faiths in public life. It exists alongside var- ious religious traditions, and its structure of beliefs is a mishmash of liberal, democratic, and socialist ideas. Its founding narrative is the Partition, and not surprisingly, the term is paired with its opposite—communal. The literature on secularism and communalism is extensive, and I will not refer to it here.

The domestic stabilizes virtue since the public domain is unstable and is the space where the tedious details of the workday are renegotiated. The trouble with this view is not that it is wrong but that it is incomplete. It provides a static picture of domestic processes. Intimate life is to be policed so that public appearance is main- tained. It is almost as if everyday life is held hostage. Indeed, in refracting the anxious strains of the danga, daily life is the place where its effects and the future meet.

Theoreticians of everyday life—de Certeau and Henri Lefebvre —designate the present as a screen on which power, resis- tance, and submission are negotiated. The relation between withdrawal and polit- ical domination gives the neighborhood its local character. This public domain is characterized by an absence of secularity. For Shamim, it is not only that the public space of his neighborhood is emptied Downloaded from jmm. He now positions himself as a spectator in the public. He does not participate in public life as much as he steels himself to observe it.

It is in this light that we can understand his injunction to discipline himself and his children to silence in public. Silence in the public area of his neighborhood is a means of withdrawal, and it is in this space that his codes for interpreting emotional expression are also codes for isolation from others. It is open to and solicits alien influences. But, by the same reasoning, such spaces can also lead to an extraordinary exclu- sion. We see this in Dharavi where it is difficult to find Muslim men gath- ered in public spaces, except mosques.

For Shamin, public space is a passage characterized by insecurity. He understands the instabilities and incertitude initiated by violence that through the danga in earlier spaces, such as the maidan, could be refashioned. The story that Shamim tells about his neighborhood in relation to the danga shows that the former was premised on a structure of feelings that the violence deliberately erased.

This story also gives him a locational identity that is tied to his immediate environmental context. However, this identity is not limited to what Appadurai calls a carceral notion of a static and bounded local. It intersects with the history of the nation-state after The next section explores how neighborhood spaces receive the nation during communal violence.

To gauge the density of everyday commu- nalism, it is important to arrive at an understanding of its peaceful and banal incarnation and at a thicker description of its spatiality, particularly at the level of the neighborhood and the family. The neighborhood here is a relay that reproduces the world of the indoctrinated ideological worker.

Search Our Site

As a relay, the neighborhood congeals into the larger formation of Hindutva nationalism, a point that is also argued by Hanson He says that the neighborhood and the everyday interactions within it are marked by a fundamental separation, Downloaded from jmm. Both Deshpande and Hanson argue that during riots, neighborhoods are the local territories over which violence is enacted.

This view is analytically incom- plete. We need to understand how neighborhoods actively produce and repro- duce the possibilities of communalism. To this end, I will schematize the spatial character of Dharavi neighborhoods and show how local signifiers acquire the value of national boundaries. In Dharavi, the neighborhood is a weaving together of rows upon rows of houses, usually one-room shacks. Space is not visual. It is not easy to separate horizon from background.

We do not find an outline, a form, or a center but a kind of labyrinth alive with the movements of crowded people. The neighborhood is filled by events, far more than by formed or perceived things. It is an intensive rather than an extensive space of distances rather than of measures and properties. Within the slum, the link between neigh- borhoods is not defined in terms of singular passageways and can be effected in a number of ways. But we can also see a second operation per- formed on the neighborhood. In its link with spaces outside the slum, each neighborhood is subject to the powers of organization.

More appropriately, the neighborhood is a space that is the product of two nonsymmetrical movements, one of which is nonvisual and local, and the other that inflects the nonvisual with the practices of naming, mapping, and quantification, as much as it shows how local geog- raphy is translated into national boundaries. One of the most powerful modes of this translation is accomplished through naming. Shamim talks of the maidan as the parliament of Pakistan.

Similarly, others invest local topography with the quality of proper nouns. Some of our boys created a diversion by attack- ing from one side, while the others put out the fire. If we put out one fire, another would start, but we made sure that it did not spread beyond the border. With one hand you give money and the other you take the plan. The apartments have come, and one day all of Dharavi will be living in them. This is the dream of everyone here.

But there is a dividing line that runs underground. Listen, these apartments will be divided on the grounds of religion—our builders, their builders; our work, their work; our food, their food. One will be called Pakistan and the other Hindustan. In , Sarvate, a Dalit Maharashtrian living in another area in Dharavi, said that during the danga, his neighborhood was known as the Hindustan-Pakistan border. A wall, about eight feet high, divided Hindustan from Pakistan and was marked by live electric wires.

In June , he said that the border had been transgressed. I am a social worker, but of late, I have lost interest. Dharavi is not what it was in the s. We lived as if in one family. Too many people pissing on everyone. See, earlier, there was a limit to where each of us lived. Yes, but there was a wall—I think I showed it to you—that separated us from them. We called it the peace line [shanti rekha]. If they did, they would be warned. The danga taught them a lesson. Before the danga, would they come here? All the time, with their tight shirts, showing muscle and abusing.

There was some talk that you were involved in the danga. I had caught two Muslim boys and I helped them return. I recognized them, they were from Chamra Bazaar, but they made a wrong turn. They were from Chamra Bazaar, but somehow they lost their way. They came from there [pointing to his left], but Chamra Bazaar is on the other side. I asked them how they had come, but they would not speak. One had blood on his head, and my shirt got his blood. I had to throw it away. What happened to them?

The others were asking for them, but I let them go. It happened here, just on the street. No muscle then, only sobs. I helped them and now these sisterfuckers stab me in the back. In those times, even sants [holy men] would have lost their heads. This is a common mode of designation in the narratives we have collected since How does one understand this mode?

Alternately, does it, as Foucault says , , mark the consti- tution of a discoursing subject whose status is juridically guaranteed as much as it is enmeshed within disciplinary mechanisms? Cogent as these arguments are, we first need to delimit how the nation-state and juridical subjects produce particular spatial forms—how the nation as an imagined community vests in neighborhoods and how speaking subjects come to embody and practice a national discourse centered around a hatred of the other.

I will explore the embodiment of subject positions in a later section. One way to do it is to imagine the nation as generated through the resources of fantasy as is argued by Axel , He shows that in response to the demand for Khalistan a separate Sikh state , the nation-state provides a horizon, both literal and fantastic, within which individuals and bodies are trans- formed into representatives of an abstract entity Axel , Through fantasy, the register of the symbolic intermeshes with the images of the people and leads to the production of a territory that has a singular and uni- fied character, one that transforms individuals into citizens Axel , This is not to argue that the state is a solid power acting unilaterally on an already con- stituted citizenry.

Dharavi residents, as the work of Roma Chatterji on housing shows, are able to pull apart the weave of the state, to act on, to enter into, and to contest its individual agencies and policies. The strand that I am pursuing here shows how recurring narratives of violence in Dharavi conceive of the state as marked by borders that are simultaneously local and national.

However, if the nation-state is produced in the neighborhood as fantasy, we need to understand how subjects present their desire at least discur- sively for the nation-state. But we do not get a sense of loss that must accompany this production. It also sees itself as the cause or the medium by which the nation- state will realize itself. The question of how this subject comes to realize the nation is left unan- swered.

We find this in Dharavi. Here, narratives of the danga shared by antag- onists emphasize the oneness of India as already constituted and a project to be realized immediately. The linking of topographic signifiers of the neighborhood with national spaces highlights the fictive, although no less real, character of the totality of India. Violence that occurs in streets, across drains, and in market places is a modality by which the history of the nation-state especially after is produced, not on but through the set- ting of the neighborhood.

This critique is not based on the instrumentality of the plan—the attempt to provide concrete houses to most, if not all, Dharavi residents and, in the process, to neutralize the hierarchies of work in the place of residence. The other cannot be reduced to particular Muslim residents who will have apartments sanctioned by the plan. The other is a structure that grounds and ensures the overall functioning of the plan as a whole. Put in another way, the other expresses the limits within which apartments in Dharavi will be inhabited.

This limit is a response, not merely to the issue of housing in Dharavi, nor even to individual Muslims occupying apartments, but to a threat that is carried in the name Muslim.

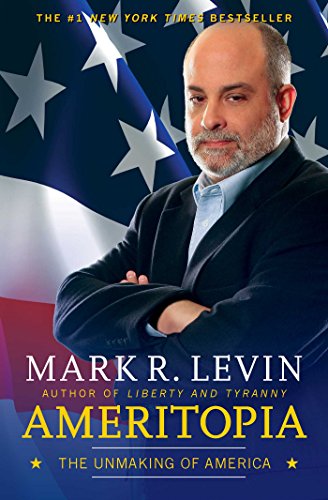

The Unmaking of Man | Publications by A-Z | Library | The Centre for Welfare Reform

The name Muslim functions as a limit in a double sense. The term marks the territorial borders of India and points us to the instabilities of the margins of identity. In his view, the danga attempted this operation. The Muslim, for Sarvate, is the inaccessible, the unknown itself, who has come within the place of habitation. Muhammad too recognizes that the term Muslim is placed within the territory of Pakistan.

The housing plan will only further this quality of being outside. Like Sarvate, he too argues that the Muslim carries within him the force of the outside, but in his account, the term is charged with irony. Through this ironic mode, the term Muslim becomes a presence that acts along the limit of the envisaged neighborhoods Downloaded from jmm. For both Muhammad and Sarvate, the name Muslim has a distinctly ide- ological function by which it is connected to the borders of India. For him, the name is an unequivocal mark of the city, its historic- ity, and the identity of its people.

To understand this mark, one needs to chart the social imaginaries of Mumbai, especially since the mark is retroactively constituted by the proper noun. To this end, Hanson histori- cizes the emergence of Hindu nationalism in the city, focuses on the prac- tices of the Shiv Sena, and pays attention to the identities that have crystallized around particular forms of naming. As used in this article, the assignment of the name is not merely a dis- cursive act. It is also a call to action.

Muslims are marked as Katua and the territories that they inhabit as outside India. How does this work in the nar- ratives? In this way, the name forms a series. This series is not a question of an association of ideas from one name to another; rather, the moral of each name consists of another name that loops back to the first. This looping back circulates on a common semantic surface and is informed by the territorial borders of India.

The folding of one name onto another seems to create an endless cycle of repetition by which the boundaries of the Indian state are spatialized in the neighborhood. In this sense, the name points us to the temporality of the riot by signaling the original moment of the formation of the Indian state. Each riot, then, must be a repetition of the Partition. But Hindu-Muslim violence is more complicated. What we find is a yoking of different temporalities in one space.

National history comes to relate to a particularized present but in a way that this present the moment of vio- lence becomes the agent of this history. The repetition of the Partition, then, is the brutal presence of the immediate—the unity of national history com- mingling with the singularity of each instance of Hindu-Muslim violence. I do not, however, mean to argue that the Partition continues in every instance of violence or that it is perpetuated or prolonged. In effect, the neighborhood becomes a political territory, which incorpo- rates materials that the nation has already gathered from the Partition.

It is also a space for the practice of everyday life, the materials for which are generated faster than history can record. This realm in which the Partition and the everyday mingle is neither a homeland nor an arena for domestic comfort but a place where residents witness the remainder of the danga— a remainder that becomes meaningful in the nexus of fantasy and national history. This transformative capacity provides temporal depth to the danga of and The violated body renegotiates in time its pres- ence both at home and in relation to the various institutions of the state.

In unraveling the force of the Partition in the life of a widow, Asha, who had lived through those days, Das shows the complex relationships of memory and amnesia not only to language but also to the body as it comes to inhabit the domestic. This section follows some of the lines of her argument.

From the perspective of this article, the repairing of relationships is constituted under the sign of injury as it marks itself on the bodies of men. Jeganathan evocatively describes the practices of violence and the terrible counterreprisals that they invite. These possibilities, described through practices of fearlessness, have micro-political locations that are mobile and inherently unstable.

In this article, it is not practices of fearlessness that allow violence to emerge but the work of time as it marks itself on the bod- ies of those who were touched by the danga. The conditions of the possibilities of violence allow us to see how vio- lated bodies in the danga circulate as political texts.

This circulation also shows us how a space for violence is carved out in everyday life. He goes on to argue that Hindu nationalist discourse attributes to the Muslim, the other, what it lacks. It is unable to achieve a fullness of being because it can define itself only in relation to the other.

- The Unmaking of a Man | Chicken Soup for the Soul.

- The Unmaking of the President 2016;

- Rickys Dream Trip to Ancient Greece!

- More stories from our partners.

- The Unmaking of Man!

Conceived thus, this space establishes the discursivity of violence and marks it with the drama of a Hindu nationalism that overcomes emascula- tion by forging national strength and self-confidence. What Hanson forgets to mention is that the corporeal body plays a crucial part in overcoming emasculation. However much he may ignore the body, it anchors his text as a vital materiality. But more than that, his argument assumes that the body Downloaded from jmm.

Our ethnog- raphy shows that for both Hindus and Muslims, the violence of and marks the body in ways in which its material fullness is disrupted. The body in the danga emerges in fragments or in the process of its effective dis- memberment and is distributed irreducibly through all the narratives on the violence.

Together with John O'Brien, we hope to encourage thinkers from many fields to collaborate to better understand how to reconcile the fundamental equality of all human beings with an appreciation for the value and wonder of human diversity. Most modern moral and political theories seem to treat diversity as a problem - but we see it as a gift - and we want to explore how communities can recognise that gift. The Unmaking of Man does not offer all the answers to that question. However it does cast some light on some of the darker parts of human history, and for me it is where much of my own thinking began.

Reflecting on the Holocaust - its horror and its causes - has been helpful in clarifying what it is we need to fight against and what is worth fighting for. In his Foreword to the book John O'Brien writes:. Those working to implement self-direction, those organizing individualised supports with the aid of The Keys to Citizenship, those using the contrast between the Gift Model and the Citizenship Model to criticise and re-shape policy will find an important branch of the root system for these useful ideas and practices here.

The content of the book is dark.

It describes how disabled people were not just swept up in the Holocaust but were in fact the first group marked for destruction by Nazi Germany. It outlines some of the parallels between the experiences of people with disabilities and other oppressed groups, especially the Jews. It goes on to describe how the factors that led to the Holocaust are still relevant today.

This is uncomfortable stuff. We like to sweep the Holocaust and eugenics into 'the past' and to hope all of that horror is done with. But sadly this is not true. As Hannah Arendt writes:. We can no longer afford to take that which was good in the past and simply call it our heritage, to discard the bad and simply think of it as a dead load which by itself time will bury in oblivion.

The Unmaking of a Man

The subterranean stream of Western history has finally come to the surface and usurped the dignity of our tradition. This is the reality in which we live. And this is why all efforts to escape from the grimness of the present into nostalgia for a still intact past, or into the anticipated oblivion of a better future, are vain.

- How To Eliminate Your Anger.

- Movable Bed Physical Models (Nato Science Series C:).

- Five Centuries of Women Singers (Music Reference Collection,).

- How FBI Director James Comey Cost Hillary Clinton the Presidency.

- .

All of this is controversial. Discussion of the Holocaust is often seen as unnecessarily extreme and many people are uncomfortable with seeing any parallels between something so evil and any contemporary events. There is a double fear, both of exaggeration and, even worse, of somehow underestimating the dreadfulness of the Holocaust itself. Of course this is not my intention.