Just as music embodies the emotional tensions within the world in an abstracted and distanced manner, and thus affords a measure of tranquillity by presenting a softened, sonic image of the daily world of perpetual conflict, a measure of tranquillity also attends moral consciousness. Negatively considered, moral consciousness delivers us from the unquenchable thirst that is individuated human life, along with the unremitting oscillation between pain and boredom.

One becomes like the steadfast tree, whose generations of leaves fall away with each passing season, as does generation after generation of people Homer, Iliad , Book VI. This fatalistic realization is a source of comfort and tranquillity for Schopenhauer, for upon becoming aware that nothing can be done to alter the course of events, he finds that the struggle to change the world quickly loses its force see also WWR , Section Schopenhauer denies the common conception that being free entails that, for any situation in which we acted, we could always have acted differently.

He augments this denial, however, with the claim that each of us is free in a more basic sense. Just as individual trees and individual flowers are the multifarious expressions of the Platonic Ideas of tree and flower, each of our individual actions is the spatio-temporal manifestation of our respective innate or intelligible character. Character development thus involves expanding the knowledge of our innate individual tendencies, and a primary effect of this knowledge and self-realization is greater peace of mind WWR , Section Moreover, since our intelligible character is both subjective and universal, its status coordinates with that of music, the highest art.

According to Schopenhauer, aesthetic perception offers only a short-lived transcendence from the daily world.

- Infantile Zerebralparese: Diagnostik, konservative und operative Therapie: Grundlagen Konservativer Und Operativer Therapie (German Edition)?

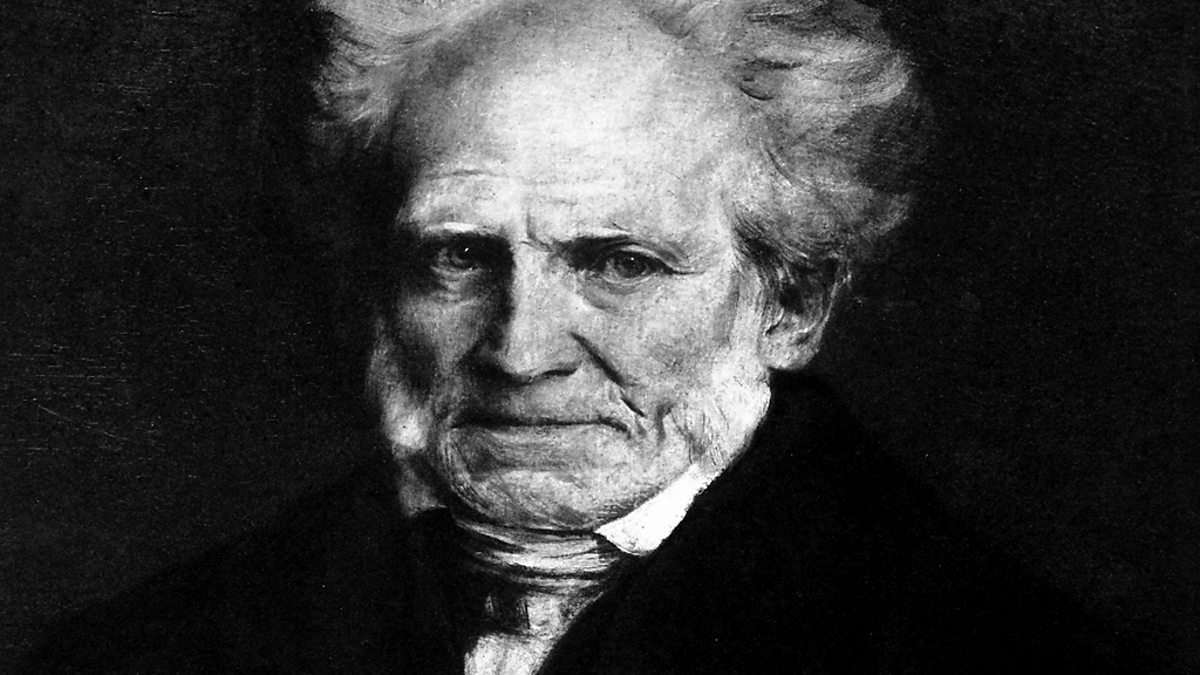

- Arthur Schopenhauer;

- The Best 99 Cent Travel Guide Available (The Finance Jock - Finance Series Book 6).

- Navigation menu?

- Philosophy Through Personal History.

- Conflict of Wills.

- Nel habla con los espíritus: Arcanus 8 (Spanish Edition).

Neither is moral awareness, despite its comparative tranquillity in contrast to the daily world of violence, the ultimate state of mind. Schopenhauer believes that a person who experiences the truth of human nature from a moral perspective — who appreciates how spatial and temporal forms of knowledge generate a constant passing away, continual suffering, vain striving and inner tension — will be so repulsed by the human condition, and by the pointlessly striving Will of which it is a manifestation, that he or she will lose the desire to affirm the objectified human situation in any of its manifestations.

The result is an attitude of denial towards our will-to-live, that Schopenhauer identifies with an ascetic attitude of renunciation, resignation, and willessness, but also with composure and tranquillity. Moral consciousness and virtue thus give way to the voluntary poverty and chastity of the ascetic. Before we can enter the transcendent consciousness of heavenly tranquillity, we must pass through the fires of hell and experience a dark night of the soul, as our universal self combats our individuated and physical self, as pure knowledge struggles against animalistic will, and as freedom struggles against nature.

One can maintain superficially that no contradiction is involved in the act of struggling i. Within this opposition, it does remain that Will as a whole is set against itself according to the very model Schopenhauer is trying to transcend, namely, the model wherein one manifestation of Will fights against another manifestation, like the divided bulldog ant. This in itself is not a problem, but the location of the tormented and self-crucifying ascetic consciousness at the penultimate level of enlightenment is paradoxical, owing to its high degree of inner ferocity.

Even though this ferocity occurs at a reflective and introspective level, we have before us a spiritualized life-and-death struggle within the ascetic consciousness. It is a struggle against the close-to-unavoidable tendency to apply the principle of sufficient reason for the purpose of attaining practical knowledge — an application that for Schopenhauer has the repulsive side-effect of creating the illusion, or nightmare, of a world permeated with endless conflict.

When the ascetic transcends human nature, the ascetic resolves the problem of evil: In a way, then, the ascetic consciousness can be said symbolically to return Adam and Eve to Paradise, for it is the very quest for knowledge i. This amounts to a self-overcoming at the universal level, where not only physical desires are overcome, but where humanly-inherent epistemological dispositions are overcome as well.

At the end of the first volume of The World as Will and Representation , Schopenhauer intimates that the ascetic experiences an inscrutable mystical state of consciousness that looks like nothing at all from the standpoint of ordinary, day-to-day, individuated and objectifying consciousness. This advocacy of mystical experience creates a puzzle: It cannot be the latter, because individuated consciousness is the everyday consciousness of desire, frustration and suffering.

Neither can it be located at the level of Will as it is in itself, because the Will is a blind striving, without knowledge, and without satisfaction. The ascetic consciousness might be most plausibly located at the level of the universal subject-object distinction, akin to the music-filled consciousness, but Schopenhauer states that the mystical consciousness abolishes not only time and space, but also the fundamental forms of subject and object: So in terms of its degree of generality, the mystical state of mind seems to be located at a level of universality comparable to that of Will as thing-in-itself.

Since he characterizes it as not being a manifestation of Will, however, it appears to be keyed into another dimension altogether, in total disconnection from Will as the thing-in-itself. In the second volume of The World as Will and Representation , he addresses the above complication, and qualifies his claim that the thing-in-itself is Will. He concludes that mystical experience is only a relative nothingness, that is, when it is considered from the standpoint of the daily world, but that it is not an absolute nothingness, as would be the case if the thing-in-itself were Will in an unconditional sense, and not merely Will to us.

In light of this, Schopenhauer sometimes expresses the view that the thing-in-itself is multidimensional, and although the thing-in-itself is not wholly identical to the world as Will, it nonetheless includes as its manifestations, the world as Will and the world as representation.

Schopenhauer: The Great Philosophers by Michael Tanner

From a scholarly standpoint, it implies that interpretations of Schopenhauer that portray him as a Kantian who believes that knowledge of the thing-in-itself is impossible, do not fit with what Schopenhauer himself believed. It also implies that interpretations that portray him as a traditional metaphysician who claims that the thing-in-itself is straightforwardly, wholly and unconditionally Will, also stand in need of qualification.

As mentioned above, we can see this fundamental reliance upon the subject-object distinction reflected in the very title of his book, The World as Will and Representation , that can be read as, in effect, The World as Subjectively and Objectively Apprehended. It can be understood alternatively as an expression of the human perspective on the world, that, as an embodied individual, we typically cannot avoid.

His view also allows for the possibility of absolute knowledge by means of mystical experience. Schopenhauer also implicitly challenges the hegemony of science and other literalistic modes of expression, substituting in their place, more musical and literary styles of understanding. His recognition — at least with respect to a perspective we typically cannot avoid — that the universe appears to be a fundamentally irrational place, was also appealing to 20 th century thinkers who understood instinctual forces as irrational, and yet guiding, forces underlying human behavior.

Yeats, and Emile Zola. The World as Will 5. Transcending the Human Conditions of Conflict 5.

Works by Schopenhauer Die beiden Grundprobleme der Ethik The Two Fundamental Problems of Ethics [joint publication of the and essays in book form]. The World as Will and Idea , 3 Vols. Routledge and Kegan Paul Ltd. The World as Will and Representation , Vols. I and II, translated by E. The World as Will and Presentation , Vol. The World as Will and Representation , Vol. Works About Schopenhauer Atwell, J. The Human Character , Philadelphia: University of California Press.

A Closer Look , Bloomington, Xlibris. The Scarecrow Press, Inc. Philosopher of Pessimism , London: New Material by Him and about Him by Dr. David Asher , Cambridge: His Philosophical Achievement , Brighton: Thinker Against the Tide , trans. Baer and David E. Virtue, Salvation and Value , Lewiston, N. The Catholic University of America Press. A Consistent Reading , Lewiston, N. A Comparative Analysis , London: University of Massachusetts Press. Translation and Commentary , Aldershot: Avebury, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.

Biographies of Schopenhauer published in English Bridgewater, P.

Schopenhauer

A Biography , Cambridge: Pessimist and Pagan , New York: Haskell House Publishers His Life and Philosophy , London: First, it is ridiculed. Second, it is violently opposed. Third, it is accepted as being self-evident. Born in Danzig and schooled in Germany, France, and England during a well-travelled childhood, he became acquainted, through his novelist mother, with Goethe, Schlegel, and the brothers Grimm. He had no friends, never married, and later became sadly estranged from his mother, a woman of considerable intellectual ability.

The essence of Schopenhauer's theory was that there are two aspects of the self: The will was a covert and distorting influence upon human character. Intellect and consciousness, in Schopenhauer's view, arise as instruments in the service of the will and conflict between individual wills is the cause of continual strife and frustration.

The world, therefore, is a world of unsatisfied wants and of pain. Pleasure is simply the absence of pain; unable to endure, it brings only ennui. His mother, however, moved to Weimar , then the center of German literature, to pursue her writing career , becoming a friend and favorite of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe - A year later, Schopenhauer and his sister joined her there. Schopenhauer himself, although on the short side, was tolerably good looking and attractive to women , but was never comfortable in romantic endeavors.

Little interested in a life of business and commerce, Schopenhauer used his private means to finance his studies. From to , he attended lectures at the University of Berlin given by the prominent post- Kantian Johann Gottlieb Fichte and the theologian Friedrich Schleiermacher - , although he reacted both against what he saw as Fichte 's extreme Idealism , and against Schleiermacher's assertion that the purpose of philosophy is to gain knowledge of God.

From until , he worked on his seminal work "Die Welt als Wille und Vorstellung" "The World as Will and Representation" and published it the following year In , Schopenhauer became a lecturer at the University of Berlin and began his lengthy opposition to fellow lecturer G. Hegel , whom he accused of among other things using deliberately impressive , but ultimately meaningless , language. He devised an ill-fated plan to schedule his own lectures to coincide with Hegel 's in an unsuccessful attempt to attract student support away from Hegel.

After the failure of this plan and an equally unsuccessful attempt a year or so later , he dropped out of academia and never taught at a university again. In , he fell in love with a year old opera singer, Caroline Richter known as "Medon" , and had a relationship with her for several years including an illegitimate child , although the child died the same year. Despite Caroline's urging, though, he never planned to marry , claiming that "marrying means to halve one's rights and double one's duties".

He lived for a time in Mannheim and Dresden , and visited Italy briefly on a couple of occasions, but eventually gravitated back to Berlin. In , at the age of 43, he again took interest in a younger woman, the year old Flora Weiss , who roundly rejected him.

An encyclopedia of philosophy articles written by professional philosophers.

After the outbreak of a cholera epidemic in Berlin in , both Schopenhauer and Hegel moved away. Hegel returned prematurely to Berlin, caught the infection, and died, but Schopenhauer settled permanently in Frankfurt in He remained there for the next twenty-seven years until his death, living alone except for a succession of pet poodles, observing a strict daily routine and taking an active interest in animal welfare. He finally received some long-awaited recognition for his early works later in the s, and his last book of somber essays and aphorisms became an unlikely best seller.

As he aged, though, his pessimism and bleak outlook on life grew almost comically excessive: It was only in his late years that Schopenhauer finally enjoyed a contentment of sorts, through his relationship with the attractive sculptress and admirer of his philosophy, Elisabet Ney - In , his health which had always been robust began to deteriorate , and he died peacefully of heart failure on 21 September , aged Schopenhauer was very much an atypical philosopher.