During the Battle of Leyte Gulf , Adm.

Navigation menu

Halsey elected to sail his main fleet from the San Bernadino Straits and throw it, in mass, upon the Japanese carriers, which proved to be decoys. In an effort never to divide the fleet, Halsey vacated San Bernadino, allowing a second Japanese force to sail through the straits, defeated surprisingly by a small if aggressive U. During the early twentieth century, the Principles of War slowly became an essential part of the military's lexicon.

Fuller, in an attempt to establish a science of war, was one of the first to codify Jomini's postulates into short, easy to understand concepts. Writing in various military journals, Fuller helped popularize their use. Urged on by the rise of corporate scientific management, American officers also searched for new ways to make warfare subject to a rational analysis. Thus, in the s, for the first time, the War Department included these principles in its training manuals. Because they were practical, logical, teachable, and above all easy to test, the principles quickly became preferred classroom topics.

Today, these lessons remain an important part of the military's educational process. Despite their popularity, some claimed the principles were not adequate in explaining war. Prussia's Karl von Clausewitz affirmed that any attempt to rationalize war into postulates was flirting with fantasy. War, he said in his unfinished work On War , was too involved with immeasurable moral and other factors to be reduced to a science. Two centuries later, America's Bernard Brodie observed that the principles provided an inappropriate insight into war's ambiguities. Finally, a few scholars claimed that violation of the principles has prompted more successful operations than when they were rigidly observed.

Had Halsey not insisted on concentrating his fleet leaving San Bernadino Strait undefended, for example, he might have prevented a vicious Japanese attack against American escort carriers off Samar Island. Despite criticisms, the Principles of War remain popular because they provide strategic planners with some basic considerations. Bernard Brodie , Strategy in the Missile Age , Weigley , The American Way of War: Carl von Clausewitz , On War , trans. I salute you for your sacrifice, integrity, and honor as you lead your people forward!

I quite like reading through a post that can make men and women think. Also, thank you for permitting me to comment! I love reading through an article that can make people think. Also, thanks for allowing for me to comment! Notify me of follow-up comments by email. Notify me of new posts by email.

Sign me up for the newsletter. From this it follows:. That we must not be easily led to use it in opening combat. Only when the enemy's disorder or his rapid retreat offer the hope of success, should we use our cavalry for an audacious attack. Artillery fire is much more effective than that of infantry. A battery of eight six-pounders takes up less than one-third of the front taken up by an infantry battalion; it has less than one-eighth the men of a battalion, and yet its fire is two to three times as effective.

On the other hand, artillery has the disadvantage of being less mobile than infantry. This is true, on the whole, even of the lightest horse-artillery, for it cannot, like infantry, be used in any kind of terrain. It is necessary, therefore, to direct the artillery from the start against the most important points, since it cannot, like infantry, concentrate against these points as the battle progresses.

A large battery of 20 to 30 pieces usually decides the battle for that section where it is placed. From these and other apparent characteristics the following rules can be drawn for the use of the different arms:. Only when we have large masses of troops at our disposal should we keep horse and foot-artillery in reserve. We should use artillery in great batteries massed against one point. Twenty to thirty pieces combined into one battery defend the chief part of our line, or shell that part of the enemy position which we plan to attack. We try first to discover what lies ahead of us for we can seldom see that clearly in advance , and which way the battle is turning, etc.

If this firing line is sufficient to counteract the enemy's troops, and if there is no need to hurry, we should do wrong to hasten the use of our remaining forces. We must try to exhaust the enemy as much as possible with this preliminary skirmish. This will deploy between and paces from the enemy and will fire or charge, as matters may be. If, at the same time, the battle-array is deep enough, leaving us another line of infantry arranged in columns as reserve, we shall be sufficiently master of the situation at this sector. This second line of infantry should, if possible, be used only in columns to bring about a decision.

On the other hand, it should be close enough to take quick advantage of any favorable turn of battle. In obeying these rules more or less closely, we should never lose sight of the following principle, which I cannot stress enough:. Never bring all our forces into play haphazardly and at one time, thereby losing all means of directing the battle; but fatigue the opponent, if possible, with few forces and conserve a decisive mass for the critical moment. Once this decisive mass has been thrown in, it must be used with the greatest audacity.

We should establish one battle-order the arrangement of troops before and during combat for the whole campaign or the whole war. This order will serve in all cases when there is no time for a special disposition of troops. It should, therefore, be calculated primarily for the defensive. This battle-array will introduce a certain uniformity into the fighting-method of the army, which will be useful and advantageous. For it is inevitable that a large part of the lower generals and other officers at the head of small contingents have no special knowledge of tactics and perhaps no outstanding aptitude for the conduct of war.

Thus there arises a certain methodism in warfare to take the place of art, wherever the latter is absent. In my opinion this is to the highest degree the case in the French armies. After what I have said about the use of weapons, this battle-order, applied to a brigade, would be approximately as follows:. Then comes the artillery, c-d, to be set up at advantageous points.

As long as it is not set up, it remains behind the first line of infantry. A strong corps would be drawn up according to the same principles and in a similar manner. At the same time, it is not essential that the battle array be exactly like this. It may differ slightly provided that the above principles are followed. So, for instance, in ordinary battle-order the first line of cavalry g-h can remain with the second line of cavalry, I-m.

It is to be advanced only in particular cases, when this position should prove to be too far back. The army consists of several such independent corps, which have their own general and staff. They are drawn up in line and behind each other, as described in the general rules for combat. It should be observed at this point that, unless we are very weak in cavalry, we should create a special cavalry reserve, which, of course, is kept in the rear.

Its purpose is as follows: Should we defeat the enemy's cavalry at this moment, great successes are inevitable, unless the enemy's infantry would perform miracles of bravery. Small detachments of cavalry would not accomplish this purpose. Cavalry moves faster than infantry and has a more demoralizing effect on the retreating troops.

Next to victory, the act of pursuit is most important in war. In order to make this corps more independent, we should attach a considerable mass of horse artillery; for a combination of several types of arms can only give greater strength. The battle-order of troops described thus far was intended for combat; it was the formation of troops for battle. That, however, does not prevent several corps from marching one behind the other on the same road, and thus, as it were, forming a single column.

The corps march according to their position in the general formation of battle. They march beside or behind each other, just as they would stand on the battle-field. In the corps themselves the following order is invariably observed: This order stands, whether we are moving against the enemy—in which case it is the natural order—or parallel with him. In the latter case we should assume that those troops which in the battle formation were behind each other should march side by side.

But when we have to draw up the troops for battle, there will always be sufficient time to move the cavalry and the second line of infantry either to the right or left. The first is that it presents obstacles to the enemy's approach. These either make his advance impossible at a given point, or force him to march more slowly and to maintain his formation in columns, etc.

Although both advantages are very important, I think the second more important than the first. In any event, it is certain that we profit from it more frequently, since in most cases even the simplest terrain permits us to place ourselves more or less under cover. Formerly only the first of these advantages was known and the second was rarely used.

But today the greater mobility of all armies has led us to use the former less frequently, and therefore the latter more frequently. The first of these two advantages is useful for defense alone, the second for both offense and defense. The terrain as an obstacle to approach serves chiefly to support our flank, and to strengthen our front. To support our flank it must be absolutely impassable, such as a large river, a lake, an impenetrable morass.

These obstacles, however, are very rare, and a complete protection of our flank is, therefore, hard to find. It is rarer today than ever before, since we do not stay in one position very long, but move about a great deal. Consequently we need more positions in the theater of war. An obstacle to approach which is not wholly impassable is really no point d'appui for our flank, but only a reinforcement. In that case troops must be drawn up behind it, and for them in turn it becomes an obstacle to approach. Yet it is always advantageous to secure our flank in this way, for then we shall need fewer troops at this point.

But we must beware of two things: They are, therefore, highly detrimental to our defense, for they do not permit us to engage easily in active defense on either wing. We shall be reduced to defense under the most disadvantageous conditions, with both flanks, a d and c b, thrown back.

The observations just made furnish new arguments for the formation in depth. The less we can find secure support for our flanks, the more corps we must have in the rear to envelop those troops of the enemy which are surrounding us. All kinds of terrain, which cannot be passed by troops marching in line, all villages, all enclosures surrounded by hedges or ditches, marshy meadows, finally all mountains which are crossed only with difficulty, constitute obstacles of this kind.

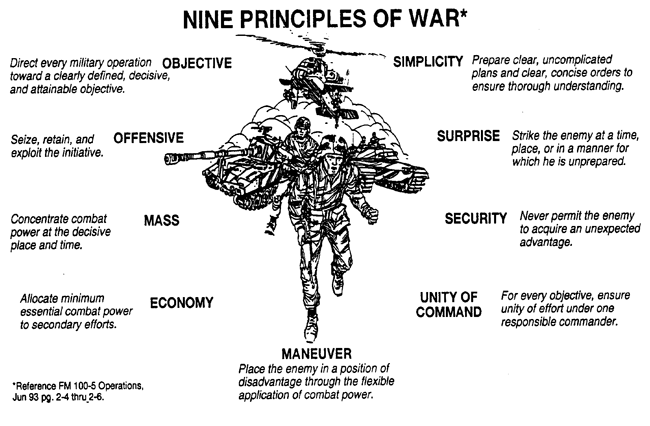

Principles of war

We can pass them, but only slowly and with effort. They increase, therefore, the power of resistance of troops drawn up behind them. Forests are to be included only if they are thickly wooded and marshy. An ordinary timber-forest can be passed as easily as a plain. But we must not overlook the fact that a forest may hide the enemy. If we conceal ourselves in it, this disadvantage affects both sides.

But it is very dangerous, and thus a grave mistake, to leave forests on our front or flank unoccupied, unless the forest can be traversed only by a few paths. Barricades built as obstacles are of little help, since they can easily be removed. From all this it follows that we should use such obstacles on one flank to put up a relatively strong resistance with few troops, while executing our planned offensive on the other flank. It is very advantageous to combine the use of entrenchments with such natural obstacles, because then, if the enemy should pass the obstacle, the fire from these entrenchments will protect our weak troops against too great superiority and sudden rout.

When we are defending ourselves, any obstacle on our front is of great value. Mountains are occupied only for this reason. For an elevated position seldom has any important influence, often none at all, on the effectiveness of arms. But if we stand on a height, the enemy, in order to approach us, must climb laboriously. He will advance but slowly, become separated, and arrive with his forces exhausted. Given equal bravery and strength, these advantages may be decisive.

On no account should we overlook the moral effect of a rapid, running assault.

It is, therefore, always very advantageous to put our first line of infantry and artillery upon a mountain. Often the grade of the mountain is so steep, or its slope so undulating and uneven, that it cannot be effectively swept by gun-fire. In that case we should not place our first line, but at the most only our sharp-shooters, at the edge of the mountain. Our full line we should place in such a way that the enemy is subject to its most effective fire the moment he reaches the top and reassembles his forces.

All other obstacles to approach, such as small rivers, brooks, ravines, etc. He will have to re-form his lines after passing them and thus will be delayed. These obstacles must, therefore, be placed under our most effective fire, which is grape-shot to paces , if we have a great deal of artillery or musket-shot to paces , if we have little artillery at this point. It is, therefore, a basic law to place all obstacles to approach, which are to strengthen our front, under our most effective fire.

Should we be very weak, therefore, we must place only our firing-line, composed of riflemen and artillery, close enough to keep the obstacle under fire. The rest of our troops, organized into columns, we should keep to paces back, if possible under cover. Another method of using these obstacles to protect our front is to leave them a short distance ahead. They are thus within the effective range of our cannon to paces and we can attack the enemy's columns from all sides, as they emerge. Something like this was done by Duke Ferdinand at Minden.

Thus far we have considered the obstacles of the ground and country primarily as connected lines related to extended positions. It is still necessary to say something about isolated points. On the whole we can defend single, isolated points only by entrenchments or strong obstacles of terrain. We shall not discuss the first here. The only obstacles of terrain which can be held by themselves are:. Here entrenchments are likewise indispensable; for the enemy can always move against the defender with a more or less extended front.

And the latter will always end up by being taken from the rear, since one is rarely strong enough to make front towards all sides. By this term we mean any narrow path, through which the enemy can advance only against one point. Bridges, dams, and steep ravines belong here. We should observe that these obstacles fall into two categories: Or we are not absolutely sure that the enemy can not turn the obstacle, as with bridges across small streams and most mountain defiles.

With very brave troops, who fight enthusiastically, houses offer a unique defense for few against many. But, if we are not sure of the individual soldier, it is preferable to occupy the houses, gardens, etc. These isolated posts serve in large operations partly as outposts, in which case they serve not as absolute defense but only as a delay to the enemy, and partly to hold points which are important for the combinations we have planned for our army.

Also it is often necessary to hold on to a remote point in order to gain time for the development of active measures of defense which we may have planned. But, if a point is remote, it is ipso facto isolated. Two more observations about isolated obstacles are necessary. The first is that we must keep troops ready behind them to receive detachments that have been thrown back.

The second is that whoever includes such isolated obstacles in his defensive combinations should never count on them too much, no matter how strong the obstacle may be. On the other hand, the military leader to whom the defense of the obstacle has been entrusted must always try to hold out, even under the most adverse circumstances. For this there is needed a spirit of determination and self-sacrifice, which finds its source only in ambition and enthusiasm.

Principles of warfare

We must, therefore, choose men for this mission who are not lacking in these noble qualities. Using terrain to cover the disposition and advance of troops needs no detailed exposition. We should not occupy the crest of the mountain which we intend to defend as has been done so frequently in the past but draw up behind it. We should not take our position in front of a forest, but inside or behind it; the latter only if we are able to survey the forest or thicket. We should keep our troops in columns, so as to find cover more easily.

We must make use of villages, small thickets, and rolling terrain to hide our troops. For our advance we should choose the most intersected country, etc.

In cultivated country, which can be reconnoitered so easily, there is almost no region that can not hide a large part of the defender's troops if they have made clever use of obstacles. To cover the aggressor's advance is more difficult, since he must follow the roads. It goes without saying that in using the terrain to hide our troops, we must never lose sight of the goal and combinations we have set for ourselves. Above all things we should not break up our battle-order completely, even though we may deviate slightly from it.

If we recapitulate what has been said about terrain, the following appears most important for the defender, i. But no defiles too near as at Friedland , since they cause delay and confusion. It would be pedantic to believe that all these advantages could be found in any position we may take up during a war. Not all positions are of equal importance: It is here that we should try to have all these advantages, while in others we only need part.

The two main points which the aggressor should consider in regard to the choice of terrain are not to select too difficult a terrain for the attack, but on the other hand to advance, if possible, through a terrain in which the enemy can least survey our force. I close these observations with a principle which is of highest significance, and which must be considered the keystone of the whole defensive theory:. For if the terrain is really so strong that the aggressor cannot possibly expel us, he will turn it, which is always possible, and thus render the strongest terrain useless. We shall be forced into battle under very different circumstances, and in a completely different terrain, and we might as well not have included the first terrain in our plans.

But if the terrain is not so strong, and if an attack within its confines is still possible, its advantages can never make up for the disadvantages of passive defense. All obstacles are useful, therefore, only for partial defense, in order that we may put up a relatively strong resistance with few troops and gain time for the offensive, through which we try to win a real victory elsewhere. This term means the combination of individual engagements to attain the goal of the campaign or war. If we know how to fight and how to win, little more knowledge is needed.

For it is easy to combine fortunate results. It is merely a matter of experienced judgment and does not depend on special knowledge, as does the direction of battle. The few principles, therefore, which come up in this connection, and which depend primarily on the condition of the respective states and armies, can in their essential parts be very briefly summarized:. To accomplish the first purpose, we should always direct our principal operation against the main body of the enemy army or at least against an important portion of his forces.

For only after defeating these can we pursue the other two objects successfully. In order to seize the enemy's material forces we should direct our operations against the places where most of these resources are concentrated: On the way to these objectives we shall encounter the enemy's main force or at least a considerable part of it. Public opinion is won through great victories and the occupation of the enemy's capital. The first and most important rule to observe in order to accomplish these purposes, is to use our entire forces with the utmost energy.

Any moderation shown would leave us short of our aim. Even with everything in our favor, we should be unwise not to make the greatest effort in order to make the result perfectly certain. For such effort can never produce negative results. Suppose the country suffers greatly from this, no lasting disadvantage will arise; for the greater the effort, the sooner the suffering will cease.

The moral impression created by these actions is of infinite importance. They make everyone confident of success, which is the best means for suddenly raising the nation's morale. The second rule is to concentrate our power as much as possible against that section where the chief blows are to be delivered and to incur disadvantages elsewhere, so that our chances of success may increase at the decisive point.

The US Army’s Nine Principles of War - Wes MD

This will compensate for all other disadvantages. The third rule is never to waste time. Unless important advantages are to be gained from hesitation, it is necessary to set to work at once. By this speed a hundred enemy measures are nipped in the bud, and public opinion is won most rapidly. Surprise plays a much greater role in strategy than in tactics. It is the most important element of victory. Finally, the fourth rule is to follow up our successes with the utmost energy. Only pursuit of the beaten enemy gives the fruits of victory.

The first of these rules serves as a basis for the other three. If we have observed it, we can be as daring as possible with the last three, and yet not risk our all. For it provides us with the means of constantly creating new forces in our rear, and with fresh forces any misfortune can be remedied. Therein lies the caution which deserves to be called wise, and not in taking each step forward with timidity. Small states cannot wage wars of conquest in our times.

But in defensive warfare even the means of small states are infinitely great. I am, therefore, firmly convinced that if we spare no effort to reappear again and again with new masses of troops, if we use all possible means of preparation and keep our forces concentrated at the main point, and if we, thus prepared, pursue a great aim with determination and energy, we have done all that can be done on a large scale for the strategic direction of the war. And unless we are very unfortunate in battle we are bound to be victorious to the same extent that our opponent lags behind in effort and energy.

In observing these principles little depends on the form in which the operations are carried out. I shall try, nevertheless, to make clear in a few words the most important aspects of this question. In tactics we always seek to envelop that part of the enemy against which we direct our main attack. We do this partly because our forces are more effective in a concentric than in a parallel attack, and further because we can only thus cut off the enemy from his line of retreat. But if we apply this to the whole theater of war and consequently to the enemy's lines of communication , the individual columns and armies, which are to envelop the enemy, are in most cases too far away from each other to participate in one and the same engagement.

The opponent will find himself in the middle and will be able to turn against the corps one by one and defeat them all with a single army. Frederick II's campaigns may serve as examples, especially those of and The individual engagement, therefore, remains the principal decisive event. Consequently, if we attack concentrically without having decisive superiority, we shall lose in battle all the advantages, which we expected from our enveloping attack on the enemy.

For an attack on the lines of communication takes effect only very slowly, while victory on the field of battle bears fruit immediately. In strategy, therefore, the side that is surrounded by the enemy is better off than the side which surrounds its opponent, especially with equal or even weaker forces. Colonel Jomini was right in this, and if Mr.

Principles of War

To cut the enemy's line of retreat, however, strategic envelopment or a turning movement is very effective. But we can achieve this, if necessary, through tactical envelopment. A strategic move is, therefore, advisable only if we are so superior physically and morally that we shall be strong enough at the principal point to dispense with the detached corps. The Emperor Napoleon never engaged in strategic envelopment, although he was often, indeed almost always, both physically and morally superior. Frederick II used it only once, in , in his invasion of Bohemia.

The battle of Kolin forced him to give up all this territory again, which proves that battles decide everything. At the same time he was obviously in danger at Prague of being attacked by the whole Austrian force, before Schwerin arrived. He would not have run this risk had he passed through Saxony with all his forces. In that case the first battle would have been fought perhaps near Budin, on the Eger, and it would have been as decisive as that of Prague.

The dislocation of the Prussian army during the winter in Silesia and Saxony undoubtedly caused this concentric maneuver. It is important to notice that circumstances of this kind are generally more influential than the advantages to be gained by the form of attack. For facility of operations increases their speed, and the friction inherent in the tremendous war-machine of an armed power is so great in itself that it should not be increased unnecessarily.

Moreover, the principle of concentrating our forces as much as possible on the main point diverts us from the idea of strategic envelopment and the deployment of our forces follows automatically. I was right, therefore, in saying that the form of this deployment is of little consequence.

There is, however, one case in which a strategic move against the enemy's flank will lead to great successes similar to those of a battle: In this case it may be advisable not to march our main forces against those of the enemy, but to attack his base of supply. For this, however, two conditions are essential:. The provisioning of troops is a necessary condition of warfare and thus has great influence on the operations, especially since it permits only a limited concentration of troops and since it helps to determine the theater of war through the choice of a line of operations.

The provisioning of troops is carried on, if a region possibly permits it, through requisitions at the expense of the region. In the modern method of war armies take up considerably more territory than before. The creation of distinct, independent corps has made this possible, without putting ourselves at a disadvantage before an adversary who follows the old method of concentration at a single point with from 70, to , men.

For an independent corps, organized as they now are, can withstand for some time an enemy two or three times its superior. Then the others will arrive and, even if the first corps has already been beaten, it has not fought in vain, as we have had occasion to remark.